New analysis of Voice and Personality

“Ten years ago the art of listening to speech hardly existed. Eyes were glutted while ears were starved. Print reached millions by their firesides, the voice a few score on hard benches in a gloomy hall. Broadcasting has changed all that.”

Professor T H Pear, Professor of Psychology, 1931

This quote is the opening from Pear’s book Voice and Personality. At the time, radio was transforming the world. Before then it would have been rare to hear someone without seeing them. What judgements do listeners make from a voice alone? This was the sort of question that fascinated Tom Hartherley Pear, Britain’s first full-time Professor of Psychology.

It lead to the most remarkable mass psychology experiment in 1927, probably the first one ever on this scale. Pear persuaded the BBC to let nine people appear on the radio where they recited a passage from Charles Dicken’s The Pickwick Papers. The Radio Times published a questionnaire and over 4,000 people sent in answers about how they perceived each of the speakers.

In my book Now You’re Talking, I outlined some of what Pear found and compared it to the latest research on voice. For example, Pear asked people to estimate the age of the talkers. What he found was that the age of young talker’s tended to be overestimated, and that of older talkers underestimated. A finding that has been backed-up by subsequent laboratory studies.

At the back of Pear’s book Voice and Personality are 632 text responses. Many are spectacularly judgemental about the speakers:

“Gave himself away by unconsciously using his evidently habitual, scolding, hectoring voice, with nasty twang (I don’t mean accent), I mean viciousness. There was nothing in the passage at all calling for that feeling. He, I am sure, is given to ranting and stirring up strife, a most bullying, unpleasant person.”

Comment on the voice of Detective-Sergeant F R Williams

Intriguingly, Pear doesn’t seem to have analysed these text responses. With the rise of Natural language processing (NLP) in computing science, there are now data-mining tools that can be used to analyse text. I thought I’d see what could be learnt from the free text responses at the back of Pear’s book using these tools.

Sentiment analysis

A common text mining technique is polarity analysis where the general emotion being portrayed is quantified to see if it is positive or negative. Broadly, it totals the number of positive words in a sentence (e.g. “happy”) and also the number of negative words (e.g. “sad”), with the difference between the two totals giving an overall measure of how positive (or negative) a sentence is. A graph of the scores for the various talkers is shown below. The bigger the purple bar, the more positive the comments about the speaker.

Polarity analysis for the nine speakers.

(Using the sentimentr package in R. Average sentiment across all responses and 95% confidence intervals)

There are clear differences between the different talkers, with Mr H Cobden Turner being written about most negatively and Miss Marjorie Pear attracting the most positive sentiments. Why?

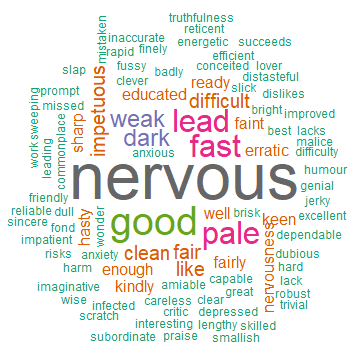

Looking at the words that underlie the sentiment scores it becomes clear. Below is a wordcloud for the remarks about Mr H Cobden Turner. These are just the words in the text that are scored by the test-mining algorithm as being important for determining sentiment. The bigger a word in the cloud, the more often it was used.

About a fifth of respondents wrote about Mr H Cobden Turner being nervous, for example:

“Young, rather nervous or careless; rather too hasty to read intelligently. Probably employed in an office where he does not get the chance of meeting educated people.”

Comment on Mr H Cobden Turner

Turner was a general manager of an engineering firm, so maybe it is unsurprising that he was nervous broadcasting live to the nation. Pear had instructed the speakers “not to rehearse the reading, but just to know what it was about.” Pear notes that “some of [the talkers] did not read it easily.” Overall, Turner’s emotional score is roughly neutral, because the words people used were split roughly evenly between positive and negative.

In contrast Miss Marjorie Pear attracted more positive comments,

“This girl, one hardly dare say woman, has much imagination, and read with good expression at times, as if she were reading for an audience of young people. She may have a pleasing manner, and cheerful disposition.”

Comment on Miss Marjorie Pear

Looking at Marjorie Pear’s wordcloud below, what leaps out is that a large majority of the words portray a positive sentiment. This would no doubt have pleased Professor Pear, as Marjorie was his eleven year old daughter!

This is the first time I’ve used sentiment analysis. It is certainly a quick way of getting some understanding of the text, and is useful for quantifying the responses and reducing subjective experimenter bias. But now I want to get a deeper understanding of the text responses. For that, I’ll need to apply some other text-mining approaches. Any thoughts what I should do next with the data? Please comment below.

You can read more about current research into how voice portrays personality, including how listeners often get it wrong, in Now You’re Talking.

Follow me

0 responses to “A remarkable 1920s experiment into the voice”

[…] ← A remarkable 1920s experiment into the voice […]

[…] in the experiment. The male group splits according to how well the passage was read. As noted in a previous blog using sentiment analysis, nervousness was an important differentiator between […]