How was it built?

Over the last 18 months I’ve been constructing a 1:12 scale model of Stonehenge. I want to better understand the ancient acoustics within the circle. By creating Stonehenge ‘Lego’ I can test how the site would have sounded in it’s various historic configurations. With so many stones displaced or missing in Stonehenge, the acoustics nowadays is very different to how it would have sounded thousands of years ago.

Basics of acoustic scale modelling

Scale models are a tried and tested technique in acoustics, with a history dating back to the 1930s [1]. For this 1:12 scale model, we shrunk all the dimensions of the structure by a factor of 12 and then tested it using sound at twelve times the frequency. The reason you increase the frequency, is to make sure the relative size of the sound waves and stone dimensions are the same in the model and the real stone circle. This is vital so the sound interacts with the model stones in a way that mimics the real site.

Testing in architectural acoustics typically happens up to about 5,000 Hz (roughly the top note on a piano). This means in the model we needed to test to at least 60,000 Hz (a long way beyond where humans can hear).

We ended up working at 1:12 scale because we wanted the largest possible model that could fit in Salford University’s semi-anechoic chamber. We could have shrunk the model further, but that would have created more measurement problems. In particular, the excessive loss of energy as sound moves through the air at ultrasonic frequencies would have caused problems.

Rock materials

For the tests to give the right answers, we need the physics in the model to be the same (at 12x the frequency), as it would be in the real space. For instance, the amount of energy absorbed by the real stones when sound reflects at 1000 Hz, has to be the same as the energy absorbed by the model stones at 12,000 Hz. This is why acoustic scale models are often made of different materials to real structures, and why the Stonehenge model isn’t made out of real rocks. Which is fortunate, because it would be very difficult to make otherwise.

I’ve been asked a few times why the floor is unfinished MDF and not artificial grass. That is to match the absorption of the ground between the model and the real Stonehenge. And the MDF isn’t painted green because it would have made the model floor too reflecting.

Most sound is lost from Stonehenge when it disappears into the sky or between the stones. As long as the model stone materials are hard and not very absorbing, then the physics will be well-modelled. More important is to have stones that are the right size, position and shape. The model drew on the Stonehenge laser scan data from Historic England [2] and the latest archaeological research to work out the ancient configurations [3].

Too many stones!

The 2200 BC model of Stonehenge I worked with has 157 different stones. I started thinking of 3D printing every stone, but that would have taken ages. Instead 27 stones that were representative of all the possible shapes and sizes were printed, and casts made to create the other 130 stones needed.

For example, the tallest trilithon (two uprights with a lintel on top) in the middle of the model is unique and a different size to anything else (see photo). So all three stones in that trilithon were individually printed (which took about ten days on a huge 3D printer). But the four other trilithons in the middle are not so different from each other in size and shape. Consequently, in the model these are duplicates. Two uprights and a lintel were 3D printed, and casting used to create the duplicates.

The 3D prints like the one above in white were originally hollow. This was done to save material and printing time. They were then back-filled with heavy material (aggregate and plaster) to make sure there was no air cavity behind. Otherwise we risked making something very sound absorbing.

To enable casting, silicon moulds was made using the 3D prints. Then a polymer-modified plaster was used to create each of the stones. Using a liquid acrylic polymer with water in the plaster mix, reduces the porosity and makes the stones much tougher.

Finally, the stones were taken to a car-paint shop who used a cellulose paint to finish them. This is important to fill any surface pores to reduce the acoustic absorption.

Setting out the stones

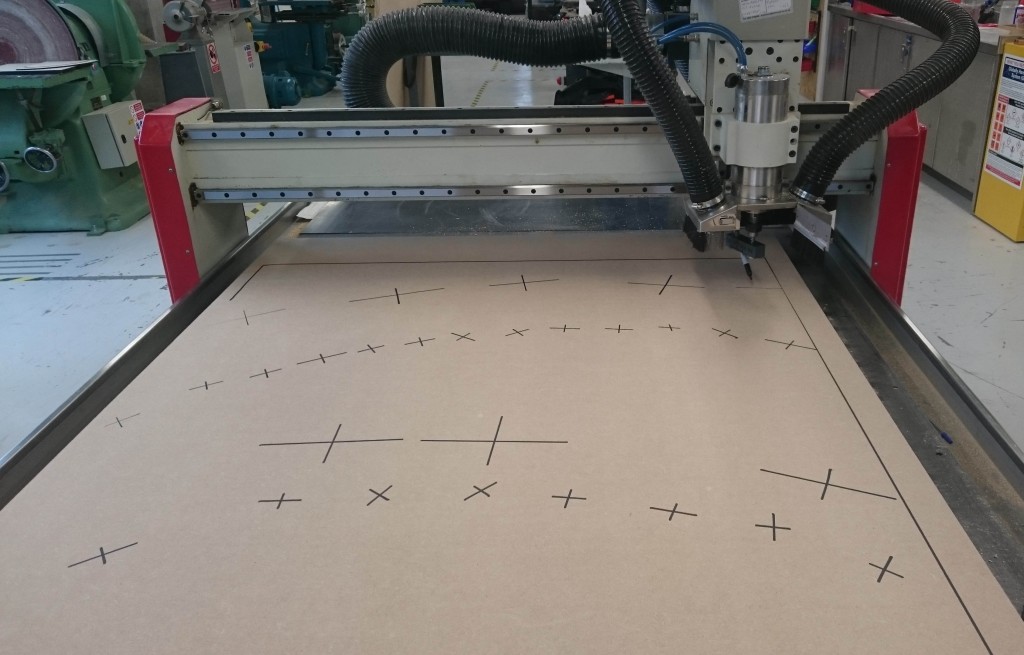

Placing the stones in the right position was also a mammoth task, but a neat trick made it easier. We turned a large CNC machine into a pen plotter and used that to draw out the location of the stones on the MDF ground boards using a sharpie.

Even so, it was quite a slow process to set up the stones for acoustic testing. It took about a day. Once the stones were all in place and the lintels placed on-top, any joints between the stones had to be sealed. I used play dough for this. If I was to do this again, I’d use pre-warmed Plasticine. The play dough was easier to work with initially, but over time it gradually dried out and shrunk.

How long did it take?

The process was very laborious. It took about 18 months to make the model, much of it working in my spare time at weekends and during the evening. What I haven’t written about is the huge amount of time it took to take the CAD model provided by English Heritage and separate out all the stones on the computer for 3D printing and moulding.

Thanks to all the wonderful technicians and modelling experts at University of Salford who helped me with 3D printing, moulding and casting. Particularly Tim Bailey who coached me and made me a model maker.

What did the measurements show?

The results have now been published in Using scale modelling to assess the prehistoric acoustics of stonehenge, Journal of Archaeological Science (open access)

Notes

[1] Rindel, J.H., 2002. Modelling in auditorium acoustics. From ripple tank and scale models to computer simulations. Revista de Acústica, 33(3-4), pp.31-35.

[2] Bryan, P.G., Abbott, M. and Dodson, A.J., 2013. Revealing the Secrets of Stonehenge Through the Application of Laser Scanning, Photogrammetry and Visualisation Techniques. ISPRS-International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, (2), pp.125-129.

[3] Darvill, T., Marshall, P., Pearson, M.P. and Wainwright, G., 2012. Stonehenge remodelled. Antiquity, 86(334), pp.1021-1040.

Follow me

44 responses to “An Acoustic Scale Model of Stonehenge”

Thia is fascinating! Will there be any tests using real sound, transposed up and recorded, then transposed back down for an acoustic experience of a virtual walkaround? THAT would be amazing!

Lou Judson Intuitive Audio 415-883-2689

>

Yes, we did some auralisations for the BBC. When I get a spare moment I’ll be uploading them.

It’ll sound a lot different if you put the roof on it.

Yep, but surprising you do get quite a lot of reverb even though it is open to the skies

Do you have any recordings of vocals played in the model sped up 12x, where the results were then slowed down 12x. Much more fun than frequency sweeps,

Equally important! Did you do all your work in a hooded robe?

We did do some auralisations. I’ll upload them when I get time to blog about this some more.

What’s behind the reason (trigger/curiosity) behind this research? Could one assume, that back in the days there’s been an attempt to plan the stone ‘arrangement’ by utilizing the physics (phenomenon) of acoustics?

All the best, Martin @ http://www.desiderata.xyz

We don’t know the intention of the builders. But whatever was intended by the design, they ended up with a structure with an unusual acoustic for its time.

BTW, absolutely fascinating! Also, the journey through 3D printing.

Acoustic “Spinal Tap”. Since he doesn’t actually report on the acoustical findings, it’s just a tease, you know, like “Spinal Tap”.

2300 Frederick Douglass Blvd, 12E NYC 10027 Or 70 Sparkling Ridge, New Paltz 12561 (212) 662.6116 [MOBILE]

[…] ← An Acoustic Scale Model of Stonehenge […]

[…] 1:12 Acoustic Scale Model of Stonehenge allows us to examine the acoustic within the stones in the 2200 BC configuration. My last blog […]

Reblogged this on sideshowtog.

[…] How it was built […]

[…] my measurements in the 1:12 acoustic scale model of Stonehenge can help quantify how useful these reflections were. Who was inside or outside the stone circle […]

[…] 1:12 physical scale model of Stonehenge allows us to examine what different parts of the structure do to the sound. We can add and remove […]

[…] plane cut through the Stonehenge model at about chest height. Real Stonehenge is 3D! So we used our 1:12 acoustic scale model of Stonehenge to see if we could measure any whispering gallery waves. Figure 10 shows the set-up for the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Cox and colleagues utilised laser scans of the website and archaeological proof to construct a bodily design a person-twelfth the dimensions of the real monument. That was the largest achievable scale replica that could suit inside of an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the web site and archaeological proof to assemble a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest attainable scale reproduction that would match inside an acoustic chamber at […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

The purpose of Stonehenge It is same of a greek romain auditorium ?

I mean is it ? 🙂

Societies were very different so the purpose was very different. But it is likely that speech and musical sounds were made in both places, because lots of human activities involve that. So they have some acoustic requirements in common.

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] La riproduzione scala 1:12 della formazione di Stonehenge (Foto@acousticengineering.wordpress.com) […]

[…] trabalha na maior réplica em escala possível construída dentro da câmara acústica da Universidade de Salford, na […]

[…] Trevor Cox and colleagues used laser scans of the site and archaeological evidence to construct a physical model one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. That was the largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the […]

[…] thing as closely as they could. They made a scale model 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) in diameter. That’s one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. It’s as big as it could be and still fit inside an acoustic chamber at the University of Salford […]

[…] thing as closely as they could. They made a scale model 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) in diameter. That’s one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. It’s as big as it could be and still fit inside an acoustic chamber at the University of Salford […]

[…] thing as closely as they could. They made a scale model 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) in diameter. That’s one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. It’s as big as it could be and still fit inside an acoustic chamber at the University of Salford […]

[…] thing as closely as they could. They made a scale model 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) in diameter. That’s one-twelfth the size of the actual monument. It’s as big as it could be and still fit inside an acoustic chamber at the University of Salford […]

[…] as closely as they could. They manufactured a scale design 2.6 meters (8.5 ft) in diameter. That is one particular-twelfth the sizing of the true monument. It’s as huge as it could be and even now in shape inside an acoustic chamber at the University […]